Mental Health and Cultural Stigma

How different cultures view mental illness—and the growing global movement toward open conversation.

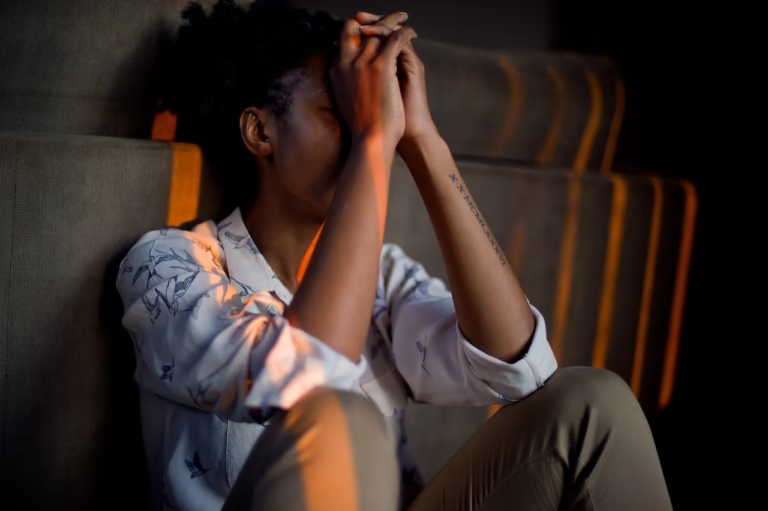

Mental illness affects people in every community around the world, but how societies understand and respond to mental health varies widely. In some places, mental health conditions are treated as medical issues and openly discussed; in others, they are stigmatized, hidden, or framed as moral failings. That difference shapes whether people seek help, how families react, what policies are prioritized, and the everyday lives of millions.

How big is the global problem?

The scale is vast. Recent global estimates show that over a billion people are living with some form of mental health condition — ranging from anxiety and depression to more chronic disorders — and many countries still lack the services and funding necessary to respond fully. This makes stigma and access to care a pressing worldwide public-health priority. 0

What do we mean by “stigma”?

“Stigma” around mental illness includes negative beliefs, prejudices, and discriminatory actions toward people who experience mental health problems. Stigma appears at several levels: public stigma (community beliefs and stereotypes), self-stigma (internalized shame), and structural stigma (institutional policies and practices that disadvantage people with mental illness). The more stigma operates, the harder it is for people to talk openly and to access care. 1

Culture shapes how mental illness is seen

Culture provides the lens through which symptoms are interpreted and described. In some East Asian cultures, for instance, emotional distress is often expressed as physical complaints and families may emphasize emotional restraint; in many collectivist societies, concerns about family reputation can discourage open disclosure. Conversely, in cultures that prize individual autonomy, people may be more likely to frame mental health as a personal, medical matter and to seek professional help. Cross-cultural research demonstrates that stigma is universal, but its expression — and its consequences — are shaped by local values and social structures. 2

Examples: how stigma shows up in different regions

Asia

In many Asian societies, social harmony and family reputation are deeply valued. Admitting to mental health problems can bring shame on the family, which pushes concerns underground. As a result, symptoms may be described as physical ailments, or people may seek help from spiritual or traditional healers before medical providers. Researchers emphasize culturally sensitive outreach — for example, integrating trusted community leaders into education campaigns — to reduce barriers. 3

Africa and the Middle East

In numerous communities across Africa and the Middle East, explanations for mental illness often blend spiritual, social, and biomedical models. Where psychiatric services are limited, families frequently rely on informal supports — extended kin networks, religious leaders, or traditional healers — and stigma can result in social exclusion or delayed access to effective treatments. Efforts that partner with local leaders and adapt messages to local belief systems have shown promise. 4

Europe and North America

Many Western nations have expanded services and public awareness campaigns in recent decades, yet stigma persists — sometimes in subtler forms such as workplace discrimination or reluctance to hire or insure those with psychiatric histories. Anti-stigma campaigns (e.g., national mental-health weeks, social-media advocacy, and celebrity disclosures) can shift attitudes, but sustained policy, workplace protections, and accessible treatment remain critical. 5

The human cost of stigma

Stigma is not just a social problem — it has measurable effects on health and opportunity. People who face stigma are less likely to look for treatment, more likely to experience social isolation, and often face discrimination in employment, housing, and education. Surveys show that a high proportion of people with mental health problems report stigma negatively affecting their lives, including work and relationships. 6

Local beliefs influence help-seeking

Beliefs about causation — whether a condition is seen as biological, psychological, spiritual, or a punishment — shape where people turn for help. For example, communities that interpret distress through spiritual frameworks may prioritize religious or traditional healing; others may prefer family-based support or primary-care services. That means mental-health systems must meet people where they are: respectful, hybrid models that include community and faith-based partners often improve uptake. 7

Evidence on what reduces stigma

Research identifies several effective strategies: contact-based interventions (meaningful interactions between the public and people with lived experience), education that corrects misinformation, and structural reforms that protect rights and access to services. Long-term, community-specific programs — not one-off slogans — are the most effective. Systematic reviews of anti-stigma interventions stress the importance of culturally tailored approaches and the role of people with lived experience in designing outreach. 8

Global movements — from awareness days to local activism

Global awareness initiatives like World Mental Health Day, and national campaigns such as Time to Change (England) and Mental Illness Awareness Week (U.S.), have helped bring mental health into public conversation. Around the world, grassroots activists—many with lived experience—are launching localized campaigns in schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods to normalize conversation and reduce shame. These movements combine policy advocacy, public education, and peer-support programs to change the environment people live in. 9

Workplaces, schools and policy: where stigma can be tackled

Stigma reduction requires structural change: workplace mental-health policies, anti-discrimination protections, school-based mental-health education, and funding for accessible services. Employers that offer confidential counseling, flexible leave, and training for managers can reduce stigma and improve productivity. Likewise, policies that increase service coverage and integrate mental health into primary care lower barriers to treatment and reduce the idea that mental illness is only a specialist’s problem. 10

Voices that change minds: lived experience and storytelling

One of the most powerful tools against stigma is personal testimony. When people with mental-health conditions tell their stories publicly — whether through media, community talks, or workplace panels — it humanizes the issue and reduces fear. Research shows contact with people who describe their recovery can reduce prejudice more than abstract educational messages. That’s why many campaigns deliberately center lived experience as a core part of their approach. 11

Practical tips for readers: how to talk, listen, and support

- Listen without judgment. Open questions and patient listening matter more than quick fixes.

- Use people-first language. Say “a person with depression” rather than “a depressed person.”

- Encourage professional help. Suggest a primary-care visit or a mental-health professional and offer to help find resources.

- Respect cultural context. Ask what help would feel acceptable to the person’s family and community.

- Share stories carefully. Public disclosures can reduce stigma, but respect privacy and safety when encouraging others to share.

Where to learn more — select resources

• World Health Organization — global mental health data and campaigns. 12

• National Institutes of Health / NCBI — culture and mental health overview. 13

• Mental Health Foundation — stigma and discrimination evidence and UK research. 14

• American Psychiatric Association — guidance on stigma and diverse communities. 15

• NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) — awareness week and community resources. 16

Conclusion — normalization as a public-health strategy

Stigma is a cultural product as much as a health problem. That means solutions must be cultural too: community-led outreach, respectful partnerships with faith and traditional leaders where relevant, and policies that expand access and protect rights. When society stops treating mental health as a secret and starts treating it as a shared responsibility, people are more likely to get help early, recover, and live full lives. The global movement toward open conversation — pushed by advocacy, research, and those with lived experience — is creating opportunities for change. But lasting progress will depend on sustained investments, culturally intelligent design, and amplifying voices that have been historically silenced. 17